Med market hit by lack of uniform fee policy

The Mediterranean landscape of marina concessions is highly varied, reflecting both political and economic dynamics. In Italy, writes Donatella Zucca, the situation is Kafkaesque.

“Unfortunately, almost every country has its own model. This brings many challenges to marinas and the industry as it makes competition unfair,” says Martinho Fortunato, chairman of the ICOMIA Marinas Group (IMG). “In very general terms, state owned marinas usually have an advantage over private marinas as they do not have to pay rent to a landlord. And, if they pay, the fee is much lower than what private concessions pay.”

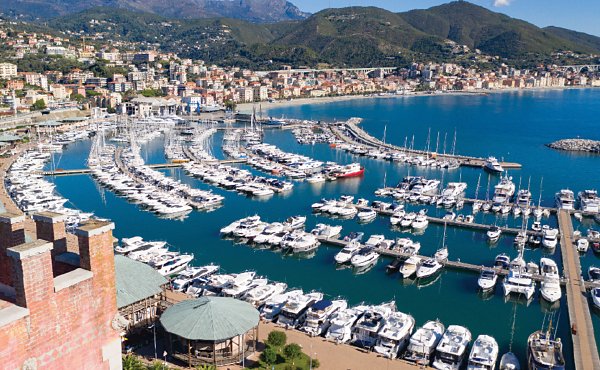

Marina di Punta Ala, like others in Tuscany, has succeeded in obtaining a review of its concession fees.

Luciano Serra: “Politicians should start thinking of yachts as privately owned masterpieces and not just the assets of possible tax evaders.”

Although unexpected rent increases can be imposed during the life of a concession, in countries such as Italy, France, Spain, Greece, Turkey and Croatia the state cannot unilaterally modify the amount of the annual fee as this has been based on a pre-agreed investment plan. “The rental fees are fixed according to the surface area occupied by the investor and can only be modified in accordance with inflation during the life of the concession.”

Basically, as Italian Marinas Association - Assomarinas - president Roberto Perocchio confirms, the most widespread practice in the Mediterranean is to establish rents based on square metre area and then ask potential investors what kind of investment they want to make. The best proposal, in terms of quality of project or other factors, wins a multi-year concession for the area in which work will be carried out. The concessionaire is the manager and the tenant.

“In the recent tender for Marina Alimos in Athens, Greece the concession fee focused on the type of investment but there are isolated incidents, such as in the Balearics, where auctions have been held to give the concession to the highest bidder,” Perocchio explains. “In Turkey, 50% of marinas are for sale and their management has been rendered uninviting by a weakening local clientele and reduced overseas visitors, and in France concession fees have not only risen but also reduced in length.”

In Italy, due to confused politics and economics, state concession fees have risen by four to five times the original cost. This enormous increase has even affected marinas with established long term contracts and has put at least 20 facilities at risk.

Marina di Varazze has escaped the penalty of hiked fees.

“The result was that, as from 2007, we had to pay €360,000 a year plus 10% regional tax – so, over €400,000. Since 2007 we’ve paid €3,600,000 as well as extra charges, penalties and surcharges. We have, of course, made every possible appeal but until a law is passed that excludes marinas with pre-2007 contracts we are blocked and at risk of failure.”

To add to the problem, since 2002 concessionaires have also had to pay a municipal tax (the IMU) on buildings for the entire length of the concession.

Some marinas – such as Marina di Varazze, Porto San Vito in Grado and, most particularly, Porto Carlo Riva in Rapallo – have escaped the lash but others have had to fight. Marina di Punta Ala, Cala de Medici, Marina Scarlino and many others in Tuscany have succeeded in obtaining reviews. “We gave various reasons in our dispute, the Constitutional Court and the TAR (regional administrative court) have proved us right. Accordingly, the municipal administration issued new orders according to lower criteria, but different from those of the concession release in 1976,” says Marco Conti, director of Marina di Punta Ala.

Giorgio Casareto, director of Marina di Varazze, confirms that fee increases were made but the marina took action in the civil court and the TAR. As a result, the fee was reduced. “Maybe, like others, we have pushed proceedings in the right direction,” he says.

Marina di Rimini has been severely affected, its pre-agreed contract has been overruled and increased fees have run into several million euros.

In Italy, tourist ports have needed regulatory clarifications for a decade, they’ve been penalised by a crisis in nautical tourism and by a state administration with accountancy problems.

Roberto Perocchio sums up the situation: “Further to a ministerial decree in 1998 that favoured the construction of marinas, from the 1990s to the early 2000s the Italian Government has accepted investor’s proposals to build on state-owned land and defined this with formal concession deeds that contained a fixed and indexed fee, to be paid until the end of the concession. State fees were modified in the 2007 budget for marinas and tourist ports with existing contracts.”

“This has been disputed with success but several marinas are still in legal proceedings despite having won first and second judgements. This can still mean six or seven years of waiting before the end of the dispute so they don’t know what renovations to do,” he explains.

Although there are some areas of clarification, the Mediterranean doesn’t have uniform policies and this is even more pronounced in Italy where medium and long term policies for recreational boating are lacking despite the overwhelming importance of the nautical industry.

“Politicians should start thinking of yachts as privately owned masterpieces and not just the assets of possible tax evaders,” asserts Luciano Serra, president of Assonat – the National Association of Landing and Tourist Ports. “There has been no concrete dialogue regarding state-owned concessions. Furthermore, the previous government gave a 15 year deadline for the reform of state property concessions and it is unclear whether this applies just to bathing establishments or also to marinas. In certain regions the rule is applied to marinas and in others it’s not.”