Electric propulsion – a solution to pollution?

by Oscar Siches

Virgil, in The Aeneid (Virgil, Aeneid, II, 49), proclaimed “Whatever it is, I fear the Greeks bearing gifts” when recounting the Trojan War and the Greeks’ deception with the wooden horse. This cautionary tale is still relevant, warning us about seemingly harmless things or actions that could have hidden, unexpected consequences. Today, 2,000 years later, I’m going to flag up Virgil again and say “beware of electric propulsion and its promise to be a universal solution to pollution.”

Ecolution solutions.

Electric propulsion is undoubtedly a solution to pollution caused by emissions, but the marketing of this apparent miracle-solution fails to mention potential issues that could make the practical use of electric boats less rewarding than promised.

Power sources

The most advanced types of electric recreational boats currently rely on two power sources: fuel cells and batteries. While fuel cells are associated with hydrogen, they can also work with ethanol, diesel oil, gasoline or gas, with varying emissions and fuel efficiency/power output.

Ecolution solutions 300 bar hydrogen containers (left).

Fuel cells are stackable, and power can be increased by adding more cells. The cells themselves are relatively small, with a 30kW (40hp) cell the size of a standard laser printer. The good news? This year, Neo Orbis will be launched in Amsterdam, and it will be the first boat in the world using hydrogen from a powder source (sodium borohydride). This is a big step forward.

In June 2022, I was aboard a 20m (66ft) sailboat in Sneek, the Netherlands, that had two 30kW cells and two 20-litre hydrogen tanks each at 350 bar. With 40 litres of hydrogen, the boat could travel 100 miles at eight knots, outperforming a conventional engine four to one. However, the lack of hydrogen refuelling stations is a major obstacle to widespread adoption, and hydrogen propulsion is currently three times more expensive than diesel.

Battery power

One of the first things that users may notice is that the real autonomy of the batteries is often less than advertised. As for cars, calculations for battery life are made under ideal weather conditions and at an ideal battery temperature. However, when batteries become hot, they lose their ability to deliver energy. If the boat is heavily or unevenly loaded, it will demand more power from the engine, which will in turn require more power from the batteries. Therefore, every sailor must become familiar with the new propulsion system and use it with reasonable caution.

The age of a battery is based on its number of charge cycles, similar to how aeroplanes are aged by number of take-offs and landings. While batteries are not eternal, current batteries have a lifespan of between 3,500 and 5,000 charging cycles, which for weekend and vacation purposes equates to approximately 170 cycles per year. This provides a theoretical lifespan of between 20 and 35 years but batteries deteriorate throughout their lifespan, and the average lifespan of a boat battery is only five to seven years.

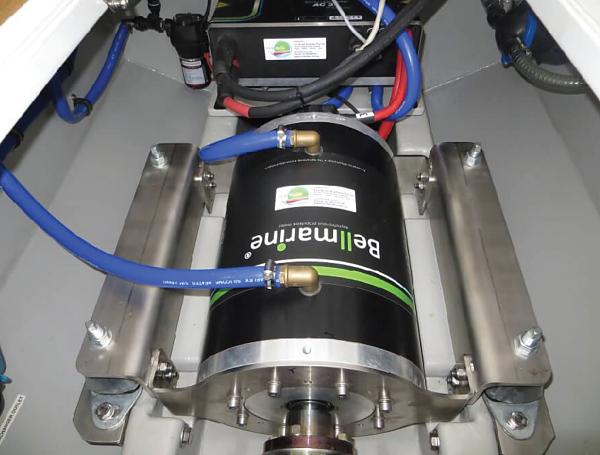

Electric motor maintenance: Ecoboats, Australia.

Charging up

Ports will also have to decide on the type and number of pedestals they install. One per boat? Not very efficient, unless one is installed for every electric vessel that spends more than six months per year in port. Slow or fast charging? In my opinion, fast charging will be necessary for port service vessels or fast passenger boats.

Batteries can be charged in three ways: via the traditional pedestal (charger on the boat, slow charging); slow charge (the charger is in the pedestal and it sends direct current (DC) to the batteries as with electric cars); and fast charging (the same method but with high amperage – a costly medium to high power electrical installation).

When electric vessels begin to proliferate, ports must install battery charging pedestals to meet the needs of the vessels that require them. Permanent/long term berth holder vessels will merit the installation of their own pedestals and transients will need to be assigned to berths that have charging ability. Why? Because few ports will be able to afford a complete electrical installation while maintaining traditional pedestals for boats with normal engines.

Training and education

TopDutch eco vessel.

Having listed some of the situations that we will encounter when adopting this technology, we still need to plan the training of port personnel. They must be trained to control and fight lithium battery fires, which require special equipment and protocols. Grouping electric boats in a specific area where there are more fire-fighting resources for lithium batteries will enhance security, as will ensuring the free passage of fire trucks to that same area.

Electric propulsion is efficient, safe, and in most cases, cheaper than hydrocarbons. It is here to stay, it will be regulated, and it will evolve rapidly in the coming years. However, we still have a long way to go to be ready to receive these vessels of the future in our ports. Knowing how to choose the system and manage well-planned and sufficient logistics is paramount. Then we can purchase an electric boat and christen it “Volta”.

.png)